DIOCESE

A Letter from Bishop Hugh Gilbert OSB

Dear Friends,

Easter is a new beginning. It’s not by chance that, in the northern half of the globe, it coincides with Spring. So much of Easter suggests this newness. The link to the vernal (spring) equinox, the connection with the Passover and its lambs, and the first Jewish month of the year, those early-in-the-morning discoveries of the empty tomb and then, overarchingly, the radiant Resurrection itself. “Behold, I make all things news” could be the title of the whole story.

EDUCATION AND FORMATION

Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul

And sings the tune without the words

And never stops – at all (Emily Dickinson).

E’en the small violet feels a future power

And waits each year renewing blooms to bring,

And surely man is no inferior flower

To die unworthy of a second spring?

John Clare, The Instinct of Spring

‘Hope does not disappoint’ (Rom 5:5). So Pope Francis began the document which opened this Jubilee Year of Hope. Why choose hope as his theme? Why, especially at a time when the world is ravaged by disease, poverty, war and even, many fear, the prospect of a Third Great War? One might be forgiven for reacting with ‘He must be joking!’ Or, more mildly, ‘What is there to hope about’? I suppose it all depends on what we mean by hope.

DIOCESE

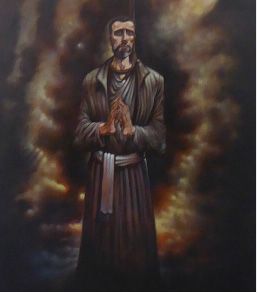

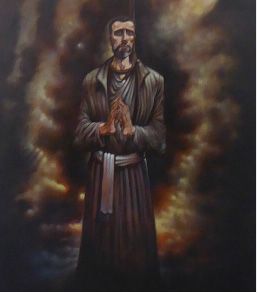

Saint John Ogilvie Pilgrimage and Mass

James Quinn SJ, vice postulator for the cause for the canonisation of Saint John Ogilvie, penned a lovely hymn in honour of Saint John Ogilvie which begins,

“Let Scotland’s hills and straths and glens

acclaim their son whose praise we sing;

who died a martyr true as steel,

a faithful knight of Christ his King.

John Ogilvie, you prayed for light,

and travelled far your pilgrim way,

to find in Scotland’s ancient faith,

the dawn of everlasting day.”

Latest Issue of the Light of the North ...

A Letter from Bishop Hugh Gilbert OSB

And how does this translate into our own lives? What will renovate me? “Hope springs eternal in the human breast”, wrote the poet Alexander Pope. When hope “springs” up in us, we are renewed. We could say that hope, authentic hope, is to the human soul what Spring is to nature. It can mean the end of an inner winter, a change of emotional colour and climate, a sense of rising energy.

Everyone knows what it is to hope, Pope Francis has said. “Where there’s life, there’s hope”, as the saying has it. And if hope, according to the classic definition, is the expectation of good things, what a range of objects it can reach for! It can mean hoping for a good dinner at the end of a hard day or the cessation of global warming. It can be a very personal, private, perhaps inexpressible thing or look to the great, common goods of peace, social justice, the well-being of the planet. It can be generous and inclusive or, sadly, narrow and vengeful. We can hope wrongly. We can be the prey of illusions. We can, in the wake of disappointments, reduce our expectations to a kind of minimum, living “lives of quiet desperation”. Or we can look at the stars like Abraham and “hope against hope.” Be that as it may, an absence of hope means the triumph of fear, lethargy, depression. Its presence means life. “Hope springs…”

What this Jubilee year looks to, with its Pauline refrain of “hope does not disappoint” and its portrait of believers as “pilgrims of hope”, presupposes this shared human experience. But it has in mind something more. It’s that “more” felt by the early Christians, referred to again and again in those writings of theirs we call the New Testament and never absent from the Church. They called this hope “living”, “blessed”, “good”, “better”. It changed their outlook and life.

It is a hope with at least these seven characteristics:

- a hope not in opposition to our natural instinct to hope, but enabling us to assess and rearrange our natural aspirations, purifying them when necessary, corroborating everything valid in them, and opening broader horizons beyond them;

- a hope from above, a gift, which theology would later call an infused theological virtue, given to us in baptism, strengthened in confirmation, fed in the Eucharist and revived in the Sacrament of Reconciliation, kept alive by the Holy Spirit;

- a hope which casts its anchor firmly in the living God, way beyond any natural resilience of our own, and so is sure and certain;

- a hope that remembers the goodness of the original creation and doesn’t forget the promise made to Noah after sin, but which finds its strongest ground in the irreversible generosity of the Father, his unshakeable will for our good, his inability to give up on us as shown in the death and resurrection of Christ and in the gift of the Holy Spirit poured into our hearts;

- a hope that looks to the “everlasting hills” of God’s promises: the kingdom of God, eternal life, the resurrection of the flesh, the righting of wrongs and above all the coming of Christ;

- a hope that makes those that carry it people of trust and joy, able to endure ongoing evil, knowing that sin and death are not ultimates, patient waiters for the glory to come, and agents here and now of courageous, creative, constructive action, and of gentle encouragement in matters great and small;

- an Easter hope that does not disappoint.

If you have 5 minutes, listen to the “dona nobis pacem / grant us peace” of J. S. Bach’s Mass in B Minor. “Hope springs…”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v8yOP9EUIY8

Devotedly in Christ,

+

Pilgrims of Hope

Consider first the dictionary definition of the word: ‘a feeling of expectation and desire for a particular thing to happen.’ In that sense, it’s a word that we all use all the time – ‘I hope you’re well’, we regularly begin a letter or an email; ‘I hope it won’t rain tomorrow…’; ‘I do hope your operation goes well.’ It’s a word that we may use without really thinking but we use it so often – perhaps even overuse it – that we must sound like very hopeful people. Is that what the Holy Father is calling us to be when he asks us to be Pilgrims of Hope? Or is he asking more of us?

Consider the definition of hope in the Catechism of the Catholic Church: ‘Hope is the theological virtue by which we desire the Kingdom of heaven and eternal life as our happiness, placing our trust in Christ’s promises and relying not on our own strength, but on the help of the grace of the Holy Spirit’ (CCC 1817). It’s a desire not for earthly health or happiness or possessions, but for the blessed life to come in our true heavenly home. It’s a desire not only for oneself but for others as well. This is the kind of hope on which the Holy Father wants us to meditate during this special year. And it is surely a virtue which we desperately need to cultivate in our troubled times. A wise and kindly gift, then, from Pope Francis who, at the time of writing, is a shining example of hope in God’s providence and promise of eternal life, as he fights for breath in a hospital bed.

Twice before in modern times has the theme of hope been prominent in Church teaching: one of the major documents produced by the Second Vatican Council talks of hope: Gaudium et spes, joy and hope; and Pope Benedict XVI’s second encyclical was also on hope – Spe salvi, which he began thus, ‘In hope we were saved, says St Paul to the Romans, and likewise to us’ (Rom 8:24).

In the Scriptures, the word hope usually refers to hope in God’s promises, even in the midst of suffering or when darkness seems to have descended. In the Hew Testament, Christ is heralded as the one who comes from God to bring light to those who sit in darkness, to give hope to those who despair. What high hopes his disciples have in him! But then, hope quickly turns to despair when their beloved master is snatched away from them, imprisoned, tortured and crucified. Before he is taken, Jesus clearly tells them, So you have pain now; but I will see you again, and your hearts will rejoice, and no one will take your joy from you (Jn 16:22), but they don’t remember this promise – or don’t believe it – when they run away from their crucified Lord and are huddling in darkness and despair. Tradition narrates how Jesus, risen from the tomb, goes first to visit those huddling in darkness and despair in hell. What joy they must have felt when the light of Christ suddenly shone upon them! Then he returns to his despairing followers and the light dawns on them, both literally and metaphorically. “We had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel”, the travellers on the road to Emmaus tell the as yet unrecognised Jesus who patiently explains to them all the signs pointing towards the truth of the Resurrection. And then they recognise him in the breaking of the bread. Hope renewed, indeed.

Throughout the history of humankind, people have found reasons to hope in the darkest of situations. The Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, who survived the Nazi concentration camps, spent his time there counselling his fellow prisoners and encouraging them to find reasons to go on living, said this, ‘In some ways suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice … They must not lose hope but should keep their courage in the certainty that the hopelessness of our struggle did not detract from its dignity and its meaning.’ For some, this meaning was found in the sun that continued to rise each morning; for others it was the certainty that God was suffering alongside them. For himself, it was flashes of memory of his wife, her face, her eyes, and the love they shared. She and most of his family were exterminated in the camps but, after he was liberated, he did not sink back into the darkness but wrote his famous book Man’s Search for Meaning. ‘Hope is the last thing ever lost … Despair is suffering without meaning.’

“If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied” (1Cor 15:19). St Paul always has the right word, doesn’t he? Hope in this world, in the things of this world, doesn’t make us pilgrims of hope. In fact, it can make us lose sight of who we really are, or what we are journeying towards, what we celebrate at every Mass, at every funeral – people whose true vocation, true destiny, lies in eternal blessedness with God, in a sure and certain hope of the resurrection to come. It doesn’t make us immune to moments of darkness and despair, but our hope can be strengthened by recognising glimmers of light. There are plenty of words being produced on how to live this jubilee of hope, but it doesn’t have to be a complicated process. Just look for a reason to get up each morning. Think of Emily Dickenson’s little bird singing to welcome the dawn; or of John Clare’s violet sleeping in the dark earth, waiting for the light to bring it to new life, in a new spring. The signs of the Lord’s promise are all around us; we just have to look, something perhaps to do each day of the Jubilee.

Towards the end of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, we find Frodo and Sam deep in the ‘land of shadow’, almost despairing of being able to complete what seems a hopeless task. Keeping faithful watch over his sleeping master, Sam finds a glimmer of hope in the darkness: ‘There, peeping among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high up in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and hope returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty for ever beyond its reach’ (p. 922). For stars shine only in the darkness.

‘O Mary, my hope, O Mother undefiled, fulfil to us the promise of this Spring’ (St J. H. Newman)

BY EILEEN CLARE GRANT

Saint John Ogilvie Pilgrimage and Mass

These verses give a beautiful backdrop for the pilgrimage walk through the glens and hills of Scotland and

Pope Francis wrote in Spes Non Confundit, the Bull of Indiction of the Ordinary Jubilee of the Year 2025, that “Pilgrimage is of course a fundamental element of every Jubilee event. Setting out on a journey is traditionally associated with our human quest for meaning in life. A pilgrimage on foot is a great aid for rediscovering the value of silence, effort and simplicity of life” (5). As they walked, the pilgrims experienced these truths as they spent time getting to know each other, praying, enjoying the beauty of God’s creation, and widening their perspective on life. Several pilgrims also expressed an appreciation for the time they walked in silence.

The day began with reflections on pilgrimage by Sister Angela Marie OP and Oscar Matheson, a Craig Lodge missionary and member of Saint Sylvester’s Church in Elgin. Oscar noted that “pilgrimages should make us meditate on our lives. They also highlight the areas where we’ve fallen short… and areas that need pruning and purifying.” He then added that “pilgrimages have also helped me grow in obedience to God’s will in my life and helped me let go of the things of the world and follow him.” Pilgrimages also are opportunities to rely on others. The pilgrims discovered this in a particular way when they realized that they would not make it to Keith for the scheduled two o’clock Mass. Almost a dozen recovery vehicles descended upon them near Newmill, in what felt like a Dunkirk rescue mission, to collect pilgrims in small groups and drive them the rest of the journey. The pilgrims were grateful for the help of these kind people. The pinnacle of the day was a lovely Mass presided over by Bishop High Gilbert OSB, who preached about every person’s call to be a saint. Lastly, a delicious soup meal was provided by the parishioners of Saint Thomas’ Church.

Pope Francis wrote in Spes Non Confundit that the martyrs provide the most convincing testimony to hope: “Steadfast in their faith in the risen Christ, they renounced life itself here below, rather than betray their Lord” (20). As the pilgrims walked, “prayed for light and travelled along the pilgrim way,” we hope that Saint John Ogilvie’s sacrifice will continue to inspire each person and fill them with hope, just as their youthful presence at the Mass filled the people of the diocese with hope for the future.

John Paul de Quay's equine take on the life of St John Ogilvie SJ, first published in 'Jesuits and Friends' magazine, gives us a new way to appreciate the martyr's story. See page 24.

BY SR BERNADETTE MARIE OP